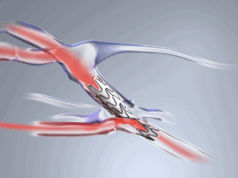

Clotted haemodialysis accesses can spontaneously recanalise following a failed thrombectomy and subsequent abandonment, a retrospective review of 3,137 mechanical thrombectomy procedures has found. The study was presented at the 2021 meeting of the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR; 20–26 March, online).

Using data on 11,266 haemodialysis access interventions over a 19-year interval, the review identified a subset of 246 failed thrombectomies and found that 14 underwent recanalisation—including seven that did so spontaneously, without requiring additional secondary procedures.

According to Ansar Vance, the review’s corresponding author and an assistant professor of interventional radiology at Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System (Philadelphia, USA), the phenomenon of spontaneous recanalisation has the potential to prevent thrombectomy patients needing a new, and unnecessary, surgical access.

The group found that there is existing literature demonstrating spontaneous recanalisation of intracranial or lower extremity arteries, but none specifically for thrombectomies performed on arteriovenous fistulae and grafts.

While 2,891 (92.2%) of the 3,137 thrombectomy procedures were completed successfully, the remaining 246 were identified as having failed, and been abandoned, due to no further attempted thrombectomy procedures being planned.

A retrospective analysis of these cases, which included 99 native fistulae, 120 grafts, nine hybrid access types, and 18 procedures without documented access details, found that 14—5.7% of the total failures—demonstrated recanalisation.

This enabled access to the blood vessel to be salvaged, even after a previous failed thrombectomy and resulting access abandonment. The review found a common feature that all 14 accesses exhibited a trace amount of blood flow beyond the site of arterial anastomosis at the time of the failed thrombectomy.

“We found that the time it took to see spontaneous recanalisation varied, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months,” Vance added.

“The majority of cases were found by physicians during follow-up visits or during haemodialysis sessions. It may also be a good idea to mention the possibility to the patients as well, as they usually know better than anyone else what their accesses feel like. If they are able to detect progression or improvement of a signal in their access, they may be able to aid in salvage.”

The review also found that all 14 salvaged accesses were successfully used for haemodialysis within 30 days after the recanalisation had taken place.

Seven of these cases demonstrated a capacity for spontaneous recanalisation, meaning additional intervention was not required beforehand, while seven patients did require secondary procedures to maintain access function—including three repeat thrombectomies with angioplasty, one thrombectomy followed by a stent, one angioplasty alone, and one with angioplasty followed by a stent.

“With a trace amount of flow restored in an abandoned access, we hypothesise that the patients’ endogenous plasmin plays a key role in spontaneous recanalisation,” Vance added.

“The cohort only includes 14 patients at this time so it is difficult to make a determination as to how long we should await the possibility of this phenomenon prior to planning a new access for these patients. Given the findings, we think it is certainly an important discussion to be had with the interventionalists, surgeons, and nephrologists involved in the patients’ care to avoid rushing into placing a new access.”

While the review concluded that spontaneous recanalisation can occur in clotted haemodialysis accesses, it also stated that further evidence of this phenomenon is needed to determine if an observation period of catheter haemodialysis is warranted in the subset of patients showing trace blood flow beyond the site of anastomosis following a failed thrombectomy.