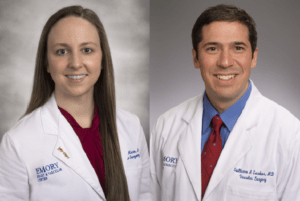

“Recycle that vein!”—that was the appeal from the authors of a new study that trialled the explantation of mature arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) from patients with venous outflow obstruction in one extremity and translocation of them to the contralateral extremity. Led by Guillermo A Escobar (Emory University, Atlanta, USA), the small study’s abstract was put to the audience at the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery (SCVS) 50th Annual Symposium (25–29 March, Miami, USA) and presented by Brandi Mize (Emory University).

The authors note that unresolvable venous obstruction in cases of a patent AVF brings extremity dysfunction and pain, traditionally followed by the ligation and disposal of a mature vein. This leads to “prolonged dialysis catheter dependence” as a new vein is sought for maturation or a prosthetic is used. They say it can be “especially devastating” when there is not an appropriate alternative vein for access as catheter dependence leads to further central stenosis. Escobar et al sought to establish whether the translocation of even “potentially aneurysmal or thrombus-laden” AVFs was an effective treatment for the swelling associated with venous obstruction as well as a means of providing “early, autologous access” to reduce patients’ dependence on dialysis catheters. They asked: “Why ligate a >10mm autologous conduit?”

The authors removed matured AVF in patients with venous outflow obstruction and repaired them ex vivo if needed. The repairs consisted of thrombectomy, endarterectomy, resection/plication of aneurysms with end-to-end reanastomosis, or any combination. Following this, they were then reimplanted in patients’ contralateral extremities to form a new AVF.

They evaluated four patients facing occluded central or extremity outflow veins despite multiple attempts at endovascular resolution. “All patients had complete resolution of their original symptoms,” Escobar et al state. All went from experiencing “severe swelling, pain and a disfigured extremity”—even with “elephantiasis and ulceration of the arm”—to having a functional access following the procedure, with a mean time to use of 44 days (median 37) and as early as 20 days in their study, though Escobar et al add that earlier access is likely “feasible in as little as 14 days”. Primary patency was a mean of 315 days (median 300). Though three of the four needed repair or partial resection of AVF aneurysms before the implantation of their fistula in the contralateral extremity, only one required reintervention in the form of angioplasty of outflow vein without interruption of dialysis.

In their conclusion, the authors state: “Translocation of mature venous conduits to new sites seem very successful even if they require repair/resection of aneurysmal portions.” They note that “surgical times are long”, as the harvest, repair and reimplantation takes a mean time of almost 8hrs. The procedure also demands “meticulous technical skill” for the repair and anastomosis of what they call “a very mismatched vein to a radial artery”, but they say that it appears to offer resolution of symptoms and the creation of a functional, autologous access.

“In addition, there is short catheter dependence compared to traditional approaches of ligation, recreation and awaiting unpredictable AVF maturity,” they add. Speaking to Renal Interventions, they suggest the findings offer a “paradigm shift” away from ligating mature AVF and instead “recycling” them: “We believe that discarding usable, autologous venous conduits should be discouraged despite the technical challenges.”