During the Vascular Access Masterclass session examining the question ‘We have new technology, but do we need it?’ at this year’s Charing Cross (CX) International Symposium (23–25 April, London, UK), attendees saw a podium first presentation from Andrew Holden (Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand) in which he shared new five-year follow-up data from the IN.PACT AV access randomised controlled trial (RCT).

During the Vascular Access Masterclass session examining the question ‘We have new technology, but do we need it?’ at this year’s Charing Cross (CX) International Symposium (23–25 April, London, UK), attendees saw a podium first presentation from Andrew Holden (Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand) in which he shared new five-year follow-up data from the IN.PACT AV access randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Outlining the primary purpose of the RCT, Holden began by asking what we know regarding long-term follow-up for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients. “We do know quite a lot at a population level about these patients,” he averred, “but results in the data are inconsistent. We don’t have any gold standard, for example, on fistula creation or maintenance and the ideal management algorithms.”

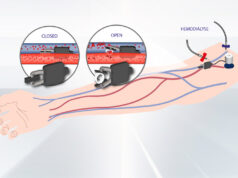

To combat this lack of knowledge, researchers conducting the IN.PACT AV RCT have published large amounts of data since 2016, starting with the study set up and primary endpoint results in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), followed by a number of subsequent publications, including some economic analyses that Holden feels “are very helpful in terms of determining the place of DCBs [drug-coated balloons] and in AV [arteriovenous] access interventions”.

Before focusing entirely on the new data from the five-year follow up, Holden first reminded the audience of the primary efficacy results that were published in the NEJM, highlighting that, “for the first time”, a DCB showed a highly significant patency advantage of 81.4% at 210 days compared to 59% for the plain balloon. Holden also pointed out that through various time points, there was not only improved primary patency for the target lesion observed, but also for the entire access circuit. As well as this, he also pointed out that “at 12 months, we saw a primary patency of 63.8%, which was significantly better that the plain balloon arm, which was reported in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology”.

Holden highlighted the economic benefits of DCBs when compared to plain-balloon angioplasty. Referring to “two important published economic analyses”, he argued that, whilst there is an upfront cost of DCBs at the index procedure, there was a cost saving due to reduced reinterventions at the three-year time point, at the study sites in the USA, Japan and South Korea.

One of the things that researchers began to notice, Holden stated, was a trend in the plain-balloon angioplasty cohort of access circuit thrombosis occurring with a higher incidence, which, at three years, had reached statistical significance. “As you can see, 18.3% versus 8.2%, a statistically significant advantage.” He continued, adding: “Some of the variables in a multivariable analysis impacted on access circuit thrombosis included previous reintervention and a higher pre-procedure diameter stenosis in an upper arm fistula. But the most powerful impact was the use of a plain balloon rather than a DCB.”

Holden then moved on to the five-year data, stating that the patients in the IN.PACT AV access study were then re-consented to allow a five-year follow-up. “As you can imagine,” he said, “there were withdrawals in both arms of the trial, because the patients had to re-consent, and some patients had passed away.” Despite this, Holden reassured the audience that they still had “good numbers out to five years” to assess vital status. In this analysis, there was no evidence of a mortality risk with DCB AV access, with Holden adding that the survival for patients who received the DCB was a little higher.

One aspect of the trial that Holden did point out was that, in both arms of the trial, the mortality was significantly lower (46.5% for plain-balloon angioplasty and 41% for DCBs) than the estimated mortality (60.4%), based on the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Holden’s reasoning for this difference was that it was likely a reflection of “patients experiencing optimal medical management in the setting of a clinical trial”.

Another question that Holden asked was why the IN.PACT AV access RCT trial had such positive results compared to other similar trials. “That’s really a long discussion,” according to Holden. “I think we should acknowledge that the trials are different in terms of patient characteristics. There are some differences in trial design and in the procedure, the quality of vessel preparation, but there’s also differences in the device. We’ve seen better patency with IN.PACT than some of the other DCBs not only in AV access, but also in other territories.”

Bringing his presentation to a close, Holden concluded by saying that: “The IN.PACT AV access trial is the only randomised pivotal trial to show consistent benefit out to 36 months. We don’t see any sign of a mortality concern, and I’d propose that the long-term data suggests that we know which device to use; the IN.PACT AV access DCB.”