The day when a urine test can inform a doctor precisely why a kidney transplant patient is experiencing organ rejection, and help to suggest the best medication for specifically addressing the problem, has become “a step closer to reality” thanks to a set of single-cell analyses that have identified “the most specific cellular signatures to date” for kidney transplant rejection. The findings are published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation (JCI) and detailed in a Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (Cincinnati Children’s) press release.

The study results, the press release states, reflect eight years of teamwork led by experts at Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati (UC) College of Medicine with contributions from researchers at the University of Notre Dame and Novartis.

Tiffany Shi (Cincinnati Children’s, Cincinnati, USA) was first author. Senior co-authors were David Hildeman, PhD, (Cincinnati Children’s) and E Steve Woodle (UC College of Medicine, Cincinnati, USA). Hildeman and Woodle co-direct the Center for Transplant Immunology at Cincinnati Children’s.

“The available treatments for stopping a rejection event have not changed much in decades. These cellular signatures open the door to establishing an entirely new set of anti-rejection therapies,” Hildeman says.

“Having a precision-medicine approach to treating organ rejection has the potential to markedly reduce the threat rejection poses to transplanted organs,” Woodle says. “More follow-up research will be needed, but these findings have implications that extend beyond kidney transplantation to potentially apply to liver, lung transplantation and more.”

Kidney transplantation is the most common form of organ transplant; provided after organ failure from diabetes, infections, injuries, and other factors. In 2022, surgeons performed 25,498 kidney transplants across the US, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). Over the past 30 years, the press release notes, gradual improvements have allowed kidney transplants to last longer so that now the ‘half-life’ for living-donor kidneys exceeds 20 years and approaches 12 years for deceased-donor organs.

“For an older person, these survival rates reflect a pretty long time,” Hildeman says. “But for younger adults and children, the chances of needing a second transplant remain high.”

However, once a kidney transplant recipient experiences acute rejection, many go on to lose their transplant and return to dialysis within 1-3 years. In addition, once a patient’s immune system rejects one organ, it is much more likely to reject a second transplant.

The tools available to effectively treat rejection—corticosteroids and antilymphocyte globulins—have remained largely unchanged for over 60 years, the press release adds. Evidence accumulated over many years has indicated that these treatments inadequately or incompletely treat rejection.

Discovering clues “one cell at a time”

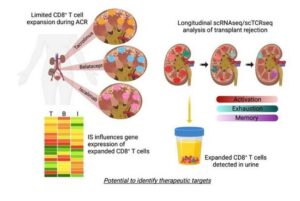

In the new study, researchers used single-cell genomic analysis technologies to compare biopsy samples from transplanted kidneys that encountered acute cellular rejection. The studies also compared rejections occurring under the commonly used maintenance immunosuppressive agent (tacrolimus) and two newer alternative medications (belatacept and iscalimab).

The “detailed” analysis meant that the team was able to track how gene expression changed within specific populations of cells that drive rejection damage, which the authors termed allospecific CD8 expanded T cell clones (CD8EXP).

The researchers say this study is the first to apply a combination of single-cell ribonucleic acid (RNA) analysis with single-cell T cell receptor (TCR) analysis to explore acute kidney transplantation rejection.

“The power of what we’re doing comes from being able to look at cells on a single-cell level. We can look specifically at the ones that are responsible for rejection and we can look at how rejection changes over time as the T cells are shifting their response to different drugs,” Shi says. Woodle, meanwhile, describes CD8EXP cells as the “tip of the spear” in rejection.

The press release identifies three “key findings”. First, even when an acute rejection event was stopped, the research revealed that treatments often are not thorough enough to eliminate all the T cells that had cloned themselves to attack the transplant. In some cases, hostile T cells persisted for months after anti-rejection treatment. This, the press release argues, suggests that multiple rejection events, previously believed to be entirely separate, may actually be one longer, “smouldering” rejection event. Addressing lurking cloned T cells that eluded initial treatment will likely require improved testing techniques and adopting more consistent practice standards.

Second, the team found roughly 20 “clonotypes” of CD8EXP T cells—from a potential of thousands—that reproduced themselves to mount attacks against a transplanted organ. The types differed according to the receptors the T cells carried. The relatively low number of clonotypes excited the researchers because it will make it easier to search for potential new treatments to stop transplant rejection.

By studying these rare, but efficient cells, the team found distinct cellular signatures occurring during a rejection event that varied depending upon which maintenance immune-suppression drug was used. The different genes involved raise the possibility of using other medications not typically associated with treating organ rejection as new weapons for specific situations.

For example, this team also recently reported success at using an mTOR inhibitor called everolimus to help patients that did not benefit from belatacept treatment. But that same drug appears to offer “no similar benefit” when tacrolimus treatment is involved, the press release states. This work led to a currently ongoing clinical trial led by Woodle to treat patients with belatacept and everolimus for maintenance immunosuppression.

Third, the same T cell types causing rejection events can also be detected in urine samples.

Why a urine test matters

Currently, obtaining the crucial details underlying rejection of a transplanted kidney requires collecting a tissue biopsy, a surgical procedure that requires visiting a hospital. Conducting multiple biopsies over time to track treatment outcomes is expensive and potentially risky for patients.

However, urine tests could be collected more frequently in a non-invasive manner and potentially without the inconvenience of visiting a hospital, the release adds. In addition to directly supporting patient care, a viable urine test would help accelerate the research work required to evaluate new anti-rejection treatment protocols. The research also demonstrated, its authors say, that CD8EXP T cells that were found in the rejecting organ were also present in the urine.

“This finding indicates that a simple urine test could substitute for a more invasive kidney transplant biopsy and thereby make it much safer and easier for patients to have their rejection treatment monitored for effectiveness,” Hildeman says.

The critical challenge for achieving a practical clinical urine test, the press release concludes, will be to establish a process that can produce test results in 48 hours, rather than the research-focused process used in this study, which took several months to complete.