Despite currently being less commonly used than metal needles in haemodialysis access, particularly in Europe, plastic cannulas offer a “useful new tool in the box” for renal nurses, thanks to their ability to lessen blood extravasation and reduce the risk of vessel wall injuries. This is according to Sabine Nipshagen, a renal nurse at B Braun via medis (Melsungen, Germany) and brand ambassador of the European Dialysis and Transplant Nurses Association/European Renal Care Association (EDTNA/ERCA).

Nipshagen presented her views on the pros and cons associated with plastic cannulas, and how they compare to their more established metal counterparts, at the 12th Congress of the Vascular Access Society (VAS; 6–9 April 2021, online). She claimed that, while the lengthy training procedures and costs plastic cannulas carry with them may be off-putting, there are a number of patient groups that stand to benefit from these devices.

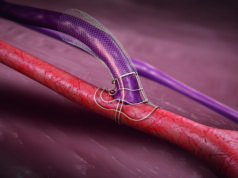

“What benefits can we expect if we invest training time and money into this new tool?” she said. “The pros associated with a plastic cannula include less blood extravasation, a reduced risk of vessel wall injury—as the instructor is smaller and removed after insertion—and the ability to cannulate the cubital fossa area. They also offer more mobility to patients and are useful in patients who are allergic to metal, or those with a fistula undergoing prolonged therapy in an intensive care unit [ICU] setting for any reason.

“The biggest challenge seems to be that we have to be consistent with learning a new technique. There is also no tubing, which can cause more movement when connecting the lines, and correction is not an option—you have to start a new cannulation at a different site. Ultrasound use is limited too, and it is much more expensive than a metal cannula, although this may change when more suppliers offer these types of cannula.”

Nipshagen began her presentation by informing VAS 2021 attendees that plastic cannulas have been commonly used in Japan for more than 30 years, and in Australia for about 10 years—but it is only in the past five years that they have become more widely deployed for haemodialysis access in Europe. In addition, they are the go-to choice of cannulation needle in other clinical settings, but metal is still currently preferred, in Nipshagen’s experience, at least, in haemodialysis.

She pointed to a paper published in the Journal of Renal Care in 2020 by Guillermo Pedreira-Robles (Department of Nephrology, Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain) et al, which assessed the experiences 163 nurses in Spanish haemodialysis units had when using plastic cannulas. Despite a substantial proportion of the nurses surveyed having little-to-no experience or training in using plastic cannulas, 55.8% of those who had previously used them rated their characteristics positively, and only 10.3% rated them negatively.

Plastic cannula characteristics that were identified favourably in the study included their anti-reflux valves and the fact they provide an alternative for patients with a metal allergy, while suggested modifications to the design of plastic cannulas included the addition of a clamping system, wings, and an improved blood visualisation system. Incidents of longer compression time, access extravasation, accidental needle removal and bruises were all, on average, reported to be less frequent when using a plastic alternative compared to a conventional metal cannula—although “impossibility of successful cannulation” was rated as more frequent when using a plastic cannula.

In addition to this study, Nipshagen reported experiences from the EDTNA/ERCA RenalPro forum, claiming that respondents she interacted with generally rated the difficulty to learn to cannulate with a plastic needle between one and four out of 10—with 10 being the most difficult—adding that it takes 10–20 cannulations to get confident with the technique, and ultrasound guidance can be useful in optimising the success of these procedures, while pain or preferences voiced by patients varied between individuals.

Nipshagen added that specific patients who may benefit from cannulation with a plastic needle include those who experience strong bleeding post haemodialysis, older patients with fragile fistulas, or those with undeveloped or new fistulas, and patients requiring cannulation in the cubital fossa region, as well as cognitively-impaired patients who are more likely to be restless and inadvertently cause their cannula to become dislodged, and ICU patients undergoing continuous veno-venous haemofiltration (CVVH) to prevent the need for a central venous catheter (CVC).

Discussing the potential downsides to using a plastic cannula, Nipshagen highlighted the fact that training nurses to use these tools can be challenging and time-consuming, and stated: “Miscannulation is frustrating for the nurse and the patient, and could cause demotivation to continue learning to use a plastic cannula. This may be a bigger obstacle than the price, so having someone who is experienced with the technique as a backup is a helpful reassurance. First of all, you have to be aware that it is a different way of cannulating—there are no wings to hold, and the cannula is slightly longer and held further back, which can cause the feeling of less control.

“Blood is visible but not pulsating, there is no possibility of correction once the cannulation is complete—you have to remove the cannula and start again—and, once the bevel is completely inside the blood vessel, you need to move it a few millimetres further in otherwise you will not be able to slide the cannula over the introducer and into the vessel.”

Nipshagen also referenced a report published in the Journal of Vascular Access (JVA) by Vicki Smith (Barwon Health, Geelong, Australia) and Monica Schoch (Deakin University, Victoria, Australia) in 2016, which stated that it took “longer than anticipated”—18 months—to fully train all 40 staff members at the Barwon Health renal department to successfully use plastic cannulas. Despite this, the same report concluded that “plastic cannulas offer a new and innovative way to cannulate arteriovenous fistulas [AVFs], and, with time, expertise and training, can be utilised to provide a successful cannulation programme for patients starting haemodialysis with AVF”.

Nipshagen concluded her presentation on a similarly measured note, claiming that the cannulating nurse should make the choice of which needle type—plastic or metal—to use based on the characteristics of vascular access, the desired blood flow, and the acute or chronic complications present at the time of the procedure. She also stated that this choice should ultimately be made with the patient in mind, in order to achieve adherence, adding that it is “worth investing in more expensive equipment” to offer the best possible care for patients with fistulas.