The arteriovenous graft (AVG) for use as a dialysis conduit is a story of innovation, disappointment, intrigue, politics and hope. A recent recalibration of guidelines from “fistula first” to the “right access” may see these easy-to-use, off-the-shelf devices move from a second-line option to take their rightful place within the treatment algorithm for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients. However, these hopes rest on reversing their reputation for being infection-prone, requiring frequent interventions and lacking durability following repeated cannulation, argues Nicholas Inston (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, UK).

Synthetic conduits were pivotal in turning renal failure from a fatal into a chronic condition. The Scribner and Buselmeier shunts gave hope of survival but were plagued by failure and complications. Then, the Brescia-Cimino fistula, described in 1966 using the wrist vessels, allowed for repeated cannulation with low infection and demonstrated improved, good longevity (Editor’s note: Michael Brescia and James Cimino were both nephrologists and the fistulas were created by the surgeon, Kenneth Appel). Despite this, many patients were unsuitable for graft implantation, and innovations in the development of grafts included biological as well as synthetic conduits.

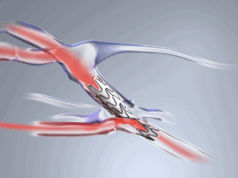

The introduction of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) as a graft material marked a major step forward in off-the-shelf options for vascular surgery, and this extended into dialysis access use. AVGs became the predominant vascular access mode in the USA—but their use as a first-line option was widely challenged. Despite good early patency, studies repeatedly showed the rates of intervention were higher with grafts than with native arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs). Infection rates and management of infection were more challenging with synthetic conduits, and overall patient survival was shown to be worse than in those with a native fistula.

Initiatives such as Fistula First and other incentives have promoted the benefits of a fistula and, whilst this is not contested, the reputation of grafts has suffered. Now designated as a second-line access in the guidelines, AVGs have developed a maligned reputation, but do they deserve this?

The main research base that these data were generated from used standard ePTFE grafts. This material, while having excellent properties, was never designed for use in dialysis patients. Repeated cannulation results in graft wall degeneration and prothrombotic tendency. In addition, material mismatch promotes stenosis at the venous outflow and frequent needling brings with it the risk of introducing infection.

As a consequence, the results associated with graft use appear poor. However, continued innovation in graft design over the last two decades has led to the development of both biological and synthetic AVGs, specifically for dialysis use. Materials like polyurethane have shown promise, but the main clinically translatable innovation has been enhancing the structure of the ePTFE layers within a graft, allowing early cannulation, with many grafts being used today with the intent of postoperative cannulation mere hours or days—rather than weeks—after access creation.

There are few quality prospective studies directly comparing these newer grafts with traditional ePTFE, or other comparators including central venous catheters (CVCs) and fistulas. Longer-term data on graft damage and degradation again are scanty.

The way that grafts are used may be just as important as the type of graft material. If grafts are used as a second-line option after fistula failure, it is likely that results, particularly regarding patient survival, will be unfavourably skewed. Lead time effect also needs to be considered, as does risk stratification to allow comparisons. Using grafts to avoid CVC deployment, either as a first access or to salvage autologous access, may influence outcomes as well as the type of graft properties required.

In patients with challenging anatomies for cannulation, a graft may be a desirable approach compared to using deeper-lying veins for a fistula—particularly when staged procedures could require a bridging catheter. We need to rethink long-held assumptions regarding vascular access grafts. Data need to be carefully scrutinised and risk adjusted. The comparators may not be fistulas, but CVCs.

The choice of graft and the timing of placement need to be considered, as do the patient’s presentation, life plan and dialysis needs, so that AVGs are considered in a more holistic, patient-driven algorithm, rather than considered as a second-line approach after exhausting fistula options.

Dialysis access is no longer suited to a ‘fistula-is-first-and-only-option’ approach, and grafts may have been maligned but their place in vascular access should not be understated. That is one of the key reasons why Renal Interventions is hosting a special AVG feature aimed at examining these questions and approaching solutions.