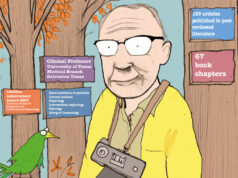

From how he started his career in interventional radiology (IR), to his work with the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), professor emeritus at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Bart Dolmatch (Mountain View, USA), speaks to Renal Interventions about his career. Touching on his inspirations in and outside of the field, Dolmatch also explores what developments in the fields of IR and kidney care interest him, and how he spends his time outside of work.

From how he started his career in interventional radiology (IR), to his work with the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), professor emeritus at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Bart Dolmatch (Mountain View, USA), speaks to Renal Interventions about his career. Touching on his inspirations in and outside of the field, Dolmatch also explores what developments in the fields of IR and kidney care interest him, and how he spends his time outside of work.

What drew you to a career in medicine and in IR?

My first “real” job after college was doing synthetic organic chemistry at the Burroughs-Wellcome Labs in Research Triangle Park, USA. It was a great experience, and I was there for almost three years. But I knew that I did not want to spend my life in the chemistry lab. My background was in both chemistry and biology, and I thought that a pivot to medicine would make sense. I applied to medical school and was accepted even though I knew very little about what physicians actually do. As I went through my clerkships at Duke University Medical Center, we would have rounds in radiology. It seemed that the radiologists enjoyed their work and were often at the centre of making a diagnosis. But during my radiology residency at University of California San Francisco (UCSF), I often found myself sitting in front of images in a dark room, and that was somewhat like being back in a chemistry lab! The solution? Interventional Radiology (IR), offering a blend of imaging, patient care, and procedural skill. I leapt for it and landed on terra firma.

Do you have a mentor who has helped and inspired you in your career?

I have had many mentors throughout my professional life. R G Lawton ran an organic chemistry lab at the University of Michigan and gave me, as a lowly undergraduate, bench space and encouragement alongside his graduate students. He would enter the lab with an enormous grin, a loud handclap, and never-wavering enthusiasm. After Michigan, I worked for Howard Schaeffer and Lil Beauchamp, my supervising chemists, at Burroughs-Wellcome where we developed Acyclovir. Howard and Lil taught me the rigours of organic synthetic chemistry and guided me in lab-based research, even though I took the job with only an undergraduate degree in Zoology. Later, during my residency at UCSF, there were many phenomenal mentors, but perhaps Ernie Ring was the most important. Not only smart and skilled, but he showed that you can be a professor and simultaneously a great guy. He also paved the way for me to do my fellowship at the Miami Vascular Institute as the first fellow at that programme, learning from Barry Katzen and Mike Dake, both pioneers in IR and terrifically important in my development as an interventional radiologist.

What recent developments in IR and kidney care excite you the most?

Over the past 20 years, care of end-stage renal patients has advanced at a slow and steady pace. But there are confounding issues that hinder progress, including the high cost of care, multi-year cycles for development of new therapies, limited reimbursement of new advances, slow acceptance of these advances by physicians, and “silos” of care amongst IRs, nephrologists, surgeons, nurses, and dialysis units. The “practice” of dialysis remains disjointed and mostly broken, with the dialysis patient stuck in the middle. Is there a better way forward for patients with renal failure?

Xenotransplantation, which has been researched in the past, was never a realistic option. But now, with CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, genetically modified porcine kidneys may be approaching reality. There have been a couple of human implants, though the outcomes have not been good, but it is not clear that the problem has anything to do with rejection of the renal xenotransplant. I am not an expert on this, but given the suffering that dialysis patients endure in a mostly dysfunctional system, it would be an amazing advance if we could implant biocompatible xenograft kidneys and move beyond dialysis (now in its 100th year).

Beside the possibility of a breakthrough in xenotransplantation, there have been catheter-based advances that can incrementally improve dialysis care, such as covered stents, drug-coated balloons, percutaneous arteriovenous fistula (AVF) creation, as well as advances in decision-making including the Kidney Failure Risk Equation, reimbursement that favours home dialysis (and peritoneal dialysis), and updated Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines. All good, but renal xenotransplantation would be great.

What is your philosophy within medicine?

What is your philosophy within medicine?

Clearly communicate. I find that most of the problems in patient care result from lapses in communication due to poor documentation in the medical record, overlooked data, lack of understanding about what we all do, limited time, stress, and many other factors. Clear communication amongst providers and patients will solve most problems. On the flip side, the daily “inbox” for most of us consumes ever more time of our days (and nights) and while good for patients, the “inbox” is not necessarily helping overworked and stressed physicians.

How has your work with SIR impacted your view of IR as a specialty?

When I was in training, most of the IR work was diagnostic angiography with some interventions in the peripheral vascular system, urinary and biliary systems. IR has now become vast. We are clinicians who deliver care in many different disciplines. I see this from my work as chair of the Renal and Genitourinary Clinical Specialty Council in the SIR Foundation. There are eight of these councils, and in our council alone, there is so much going on, including work in prostate artery embolisation for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), percutaneous AVF creation, IR treatment of renal and prostate tumours, adrenal vein sampling for hyperaldosteronism, renal transplant related IR, and many more areas.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start a career in IR?

Choose IR if it is your passion. But you must be committed to caring for patients and working collaboratively with colleagues. Learn from others and be open-minded to different approaches and new therapies. Learn to work in a team, not as a solo provider. I have become colleagues with several surgeons from outside the USA who are a team, travel abroad to learn how others do their work, and bring “best practices” back home. They are having a great time and advancing their skills simultaneously. In the USA, most of us do not visit other IR programmes for a day or two, but that experience can be invaluable. One more thought; ask a colleague to visit your IR programme to offer their critique. You would be amazed what you will learn.

What are your interests outside of medicine?

I love to travel, usually with my wife, Cindy, often combining an invited lecture with a couple of days’ exploration. We were in Greece in June for the Endo Vascular Access (EVA) meeting (Patras, Greece), and thereafter we spent a week with four other couples on an island in the Aegean. All of the guys are colleagues from the USA and Brazil, but astoundingly, the spouses got along famously, too. Best time, ever. Later this year I will be in India, Thailand, France, Portugal, as well as Eugene, New York City, Ann Arbor, Washington DC, Philadelphia, and probably Jacksonville (where we will visit Cindy’s daughter and our five-year-old grand twins). Between these trips I will be back in my clinic and at the hospital. Beyond travel, I am still an avid trail runner and ran the Santa Barbara Half Marathon this past spring with my 22-year-old son (well, we ran the same course, but he finished far ahead of me). Fly fishing and hiking are great, given time, and I have recently taken up golf to the point where I am still not good, but so far not frustrated. It is not an easy sport to learn. Fore!