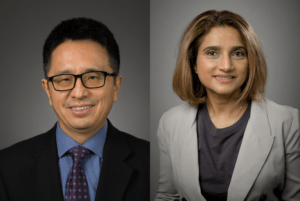

Wei Li (SUNY Upstate Medical University & Syracuse VA Medical Center, Syracuse, USA) and Mareena Zachariah (Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, USA) write to outline their vision for a new interventional nephrology programme.

Emerging in 1966 when pioneers Belding Hibbard Scribner, Stanley Shaldon, and Michael J Brescia broke ground in vascular access for haemodialysis,1 interventional nephrology (IN) has since grown, evolved, and now expanded with a wide range of minimally invasive techniques to diagnose and treat kidney-related conditions. These include vascular access creation and maintenance, thrombectomy, embolisation, and stent placement, among others. IN has become an essential component of nephrology practice, where it offers patients with kidney disease a less invasive and more efficient way of managing their conditions.

Societies, including the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology (ASDIN), have helped to provide education and training for nephrologists interested in interventional techniques since the 2000s2, during which time the IN training has been led by interventional nephrologists, mainly in private practice settings.3 There is a consensus that the future of IN will depend on the quantity and quality of its fellowship training programmes in tertiary medical centres, especially large academic medical institutions.1-5 However, as the demand for training in IN increases, IN programme directors may encounter several challenges—or even find themselves in the centre of “turf wars” in hospitals with sophisticated hierarchies and subspecialties, including endovascular and vascular surgery, and interventional radiology.

The first hurdle is patient-related factors. Patients with ESKD often have multiple other vascular comorbidities, which can increase their risk of intra-procedural complications that need immediate on-the-table surgical interventions. Another is that IN trainees need to be taught with a high level of technical expertise. There has been recent emphasis on ultrasound utilisation in IN,2,3 but unlike vascular surgeons interventional nephrologists are not currently required to possess Registered Physician in Vascular [ultrasound] Interpretation qualifications (RPVIs).

Interventional nephrologists may face challenges related to limited resources, such as access to standard operating room, specialised equipment, and imaging technologies with a hybrid setting where open surgeries can be performed simultaneously with endovascular procedures. This can make it difficult for interventional nephrologists to perform complex haemodialysis access procedures and achieve optimal outcomes for patients.

There is also a lack of standardisation. ASDIN has developed multiple clinical practice guidelines, issued current IN fellowship accreditations, and aimed to receive Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) approval for subspecialty certification.2,3,5 However, current IN fellowship graduates have not been equally recognised as other ACGME accredited fellows by hospital credentialing committees, who may raise some possible liability concerns, where interventional nephrologists are not adequately and equally as trained to perform dialysis access procedures as the vascular surgeons are. This has been particularly noted in countries like the USA, where medical malpractice is a major burden on both hospitals and physicians.6,7

Building the programme

To address the above challenges, it is essential to think via an out-of-the box strategy and expand the scope of multidisciplinary care not only in patient care but also for training future interventional nephrologists. We propose, through a collaborative effort from multiple specialties, the unique venture of an endovascular and vascular surgeon-led IN fellowship training programme.

An endovascular and vascular surgeon-directed IN fellowship training programme can provide a range of advantages to trainees looking to pursue a career in the field of IN. A surgeon-led training programme can provide IN fellows with comprehensive training, including a greater emphasis on surgical techniques as well as endovascular means of dialysis access while covering both vascular and nephrology dimensions. This can help IN trainees in becoming more skilled and confident in performing IN procedures, which can improve not only their knowledge and expertise but also their competency while bolstering their overall training experience. A vascular surgeon-led programme may offer access to specialised equipment, resources, and facilities designed for complex vascular procedures. Hands-on experience with and exposure to the latest hybrid technology and techniques can enrich their skillset.

A vascular surgeon-led IN fellowship training programme can provide a more multidisciplinary approach to care, enabling collaboration among more surgical specialties to improve patient care. The existing broad scope of vascular surgery practice has an inherent power to facilitate this among nephrologists, vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists.

By allowing vascular surgeons to lead an IN training programme, fellows may be better prepared for a variety of broader career opportunities. Furthermore, IN fellows graduating from a surgeon-led training programme have the advantage of the necessary credentials to perform certain surgical dialysis accesses, which may expand their scope of practice.

The winning strategy for such a training programme should include several key components to ensure success by focusing on providing a comprehensive and structured training programme that covers all aspects of IN. First among those is a set of clear goals and objectives. These goals should help them develop the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities to become proficient in IN procedures, rather than just as a “surgeon and nephrologist”. The curriculum, meanwhile, should cover all aspects of IN and be updated regularly to incorporate new techniques, hands-on training, and opportunities for research and scholarly activities.

High quality of care should be a top priority. The programme should ensure that the fellows have a clear understanding of the importance of patient safety, ethical considerations, and informed consent with close adherence on the current individualised and patient-centred Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guideline.8 Through the lens of social determinants of health, the programme should also advocate a culture of continuous learning, safety and professionalism while emphasising ethical conduct when caring for underserved and vulnerable patient populations.

There are pitfalls to avoid with a surgeon-led IN programme. It is important to ensure that the programme—both faculty and trainees—is diverse and inclusive in race, gender, and ethnicity. Collaborations with training programmes from other specialties should be encouraged, as should the wise allocation of cases. That is especially important when the programme faculty members also serve on other training programmes, such as vascular surgery residency/fellowship programmes—it is vital to stay away from ACGME red tape.

There is a risk of inadequate support for fellows. Such support can include financial support, access to resources, and mentorship. Good communication is critical for a successful programme, too, with clear channels in place to ensure that all stakeholders are informed and involved. The programme should avoid inflexibility and be able to adapt to the changing needs of the fellows and the field of IN.

This can include incorporating new technologies and techniques as they become available. For example, the development of the endovascular arteriovenous fistula (endoAVF) has had a significant impact on the field of IN and vascular surgery, including IN and vascular surgery training programmes. An endovascular and vascular surgeon-led interventional nephrology fellowship offers a unique training module with a “one-stop shop approach”, meaning endovascular, possible surgical arteriovenous fistula (sAVF) creation through a single visit. In addition, with a surgical capability as back-up, certain complex and challenging end-stage renal disease access cases can be achieved safely and successfully with the new technology, when patients would otherwise have been left with only a life-long central venous catheter as a dialysis option.10

Overall, an endovascular and vascular surgeon-led IN fellowship training programme can provide significant advantages for IN trainees, including a comprehensive training curriculum and exposure to complex cases, as well as enhanced collaboration with vascular surgeons and other specialties’ providers. These will ultimately improve patient outcomes. Such a fellowship also offers trainees unique professional development experience that may prepare them with better credentialing opportunities for successful future career pathways in the field.

References:

- Sachdeva B and Abreo K. The history of interventional nephrology. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2009; 16: 302-308. DOI: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.06.002.

- Niyyar VD and Beathard G. Interventional Nephrology: Opportunities and Challenges. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease 2020; 27: 344-349.e341. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2020.05.013.

- Roy-Chaudhury P, Yevzlin A, Bonventre JV, et al. Academic Interventional Nephrology: A Model for Training, Research, and Patient Care. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2012; 7: 521-524.

- Beathard GA. Change – A New Chapter in Interventional Nephrology. Seminars in Dialysis September/October 2009; 22: 564-565.

- Niyyar VD and Work J. Interventional Nephrology – Past, Present and Future. International Journal of Artificial Organs 2009; 32: 129-132.

- Phair J, Carnevale M, Wilson E, et al. Jury verdicts and outcomes of malpractice cases involving arteriovenous hemodialysis access. J Vasc Access 2020; 21: 287-292. 20190909. DOI: 10.1177/1129729819872846.

- Li W and Dissanaike S. Jury verdicts, outcomes, and tort reform features of malpractice cases involving thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2022; 75: 962-967. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.08.098.

- Lok CE, Huber TS, Lee T, et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access: 2019 Update. Am J Kidney Dis 2020; 75: S1-S164. 20200312. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.12.001.

- Quinones J and Hammad Z. Social Determinants of Health and Chronic Kidney Disease. Cureus 2020; 12: e10266. 2020/10/13. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.10266.

- Parkash S, Pena C, Cepak J, et al: Percutaneous arteriovenous fistula creation in the management of severe Hemophilia A and End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) needing hemodialysis access, and beyond, Journal of Vascular Access (In Press)